the Third Week of Lent

Click here to join the effort!

Bible Dictionaries

Watson's Biblical & Theological Dictionary

Browse by letter: A

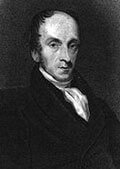

Richard Watson

Welcome to the 'Watson's Biblical & Theological Dictionary', one of the dictionaries resources FREELY available on StudyLight.org!

Containing 1,626 entries cross-referenced and cross-linked to other resources on StudyLight.org, this resource can be classified as a required reference book for any good study library.

Richard Watson was one of the greatest theologians the Methodist Church has ever known. His dictionary has proven to be a highly valuable resource even today.

All scripture references and reference to other entries within the text have been linked. To use this resource to it's full potential, follow all the links presented within the text of the entry you are reading.

If you find a link that doesn't work correctly, please use our convenient contact form. Please tell us the reference work title, entry title and/or number (this can be found in the address line), and a brief description of the error found. We will review and make corrections where needed.

You can also use this form if you have any suggestions about how to improve the usability of this resource.

These files are public domain.

Text Courtesy of BibleSupport.com. Used by Permission.